Featured Artists

Carol Law Conklin

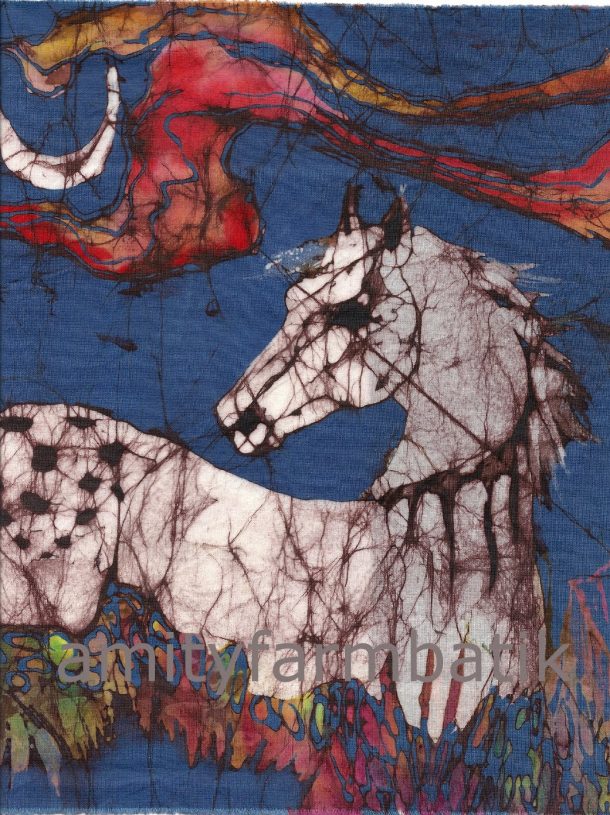

Member Carol Law Conklin, of Amity Farm Batik, writes about making batik using bleach while enjoying the summer weather:

Losing the color

It was a beautiful summer morning. Hazy and not too hot. The gentle breeze felt good as I stood at the top of the hill behind our house. Mist slowly rose and changed the soft colors of the expansive view. The mountains, arranged in subtle layers of blues, greens and purple formed the backdrop as birds and insects fill the air with their music. There is so much life this time of year. Back at home, I’m contemplating the colors I want in several batik that have already gone through many dyebaths. As the dyes are translucent, there are limits to overlays of opposite colors. In order to achieve what I want it will be necessary to bleach out some areas before the desired color can be added.

The summer weather is the best for doing discharge dyeing (bleaching). This process is something not to be done inside. The bleach, which removes the color wherever the wax has not been applied to save the design, has quite strong fumes. To stop the bleaching action, I plunge the fabric into a solution of water and vinegar, gently agitated and left there for approximately 15 minutes. This produces more toxic fumes. The commercial product, “Bleach Stop” (sodium thiosulfate crystals), is even more effective, but I believe have stronger fumes. A respirator mask is recommended when working around toxic fumes and good ventilation is essential.

Different dyes and intensities of dye bleach in a variety of unpredictable ways. When using strong solutions for bleaching deep colors be extra careful. Acid and chlorine combined can kill! Monitor and stir the fabric as it bleaches. Various fabrics and dyelots take different times. Blue seems to bleach out overly quickly and thoroughly. Some colors change to a new color and not beige or white. Silk can stand only very weak bleaching without causing the fabric to deteriorate. Vinegar has an additional bleaching action and results are unpredictable as well as fascinating.

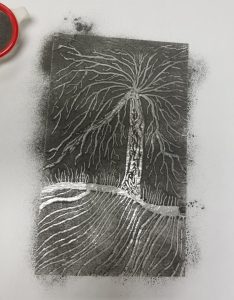

The photos show a batik in the bleaching tub, after bleaching and finally you can see my “Appaloosa Horse in Flower Field” at the top of the page after the re-dyeing and with the wax ironed out, bright and expressing the summer season.

Find more batik, articles and tutorials on Carol’s website: www.amityfarmbatik.com

Welcome to our new member, Nancy Roberts

The exhilaration of creating a piece of mosaic art led Nancy Roberts to momentary amnesia. Any mosaic artist knows that handling sharp-edged glass is an inherent danger of the form. But enraptured by the stunning iridescence of her new creation, she forgot to wear protective gloves and smoothed grout over the artwork with her bare hand. The resulting small slashes kept her from playing the piano for a week.

The exhilaration of creating a piece of mosaic art led Nancy Roberts to momentary amnesia. Any mosaic artist knows that handling sharp-edged glass is an inherent danger of the form. But enraptured by the stunning iridescence of her new creation, she forgot to wear protective gloves and smoothed grout over the artwork with her bare hand. The resulting small slashes kept her from playing the piano for a week.

Such passion is typical of creatives. Like most of them, Nancy has worked or expressed herself in some artistic way all of her life: She has written for art magazines, published her photography, designed cottage gardens and taught the history of early American architecture. (You can see the influence of architecture and her garden in her work.) And her curiosity has propelled her in many new directions. She has recently taken up the dulcimer and, of course, mosaic art. Taking a course from a local mosaic artist, Nancy immediately loved it. “It blew me away,” she says.

Tables are her favorite item to mosaic at the moment. “People throw them out and I love getting them re-glued and repaired.” Then they become a blank canvas for myriad designs in glass. She notes how a different architectural quality is evident in every table, such as old iron nails or a gracefully tapered shelf. “I try to make them look really beautiful again,” she says. She also mosaics mirrors, flat wall decorations and even a mail sorter currently hanging at VAM.

Nancy buys her materials from stained glass supply and DIY stores, often online, and she discovers mosaic materials in unusual places. A salvaged piece of a stained-glass window from a Victorian house in Saratoga Springs eventually found its way into a work titled Homage to Notre Dame, which is on sale at VAM. She also incorporates sea glass, porcelain and mirror tiles, sea shells, and vintage crockery in her work.

She enjoys the challenge of hunting down the right scraps from stained glass stores and then using those little fragments to create. Such bounty is plentiful at these shops and you can buy a boxful for a modest price, she says.

One source of her inspiration is the rolling countryside of Washington County, with its farms, fields, wetlands, and wildflowers. In fact, her next frontier in mosaics may well be landscapes, with smaller and more intricate designs. Inspiration also comes from the pleasing lines of historic architecture. Having studied early American architecture, Nancy says, “I can’t walk down the street without seeing the intricate details of houses and I see that wherever I go.” Much of her inspiration is from her extensive garden (where she grows pawpaw fruit trees as well as vining Arctic kiwis and kale). Favorite flowers — rose campion, irises and daffodils — grace some of her work. The natural world is her muse, leading her also to portray seascapes and the brilliant forms of butterflies. The adventure of learning something new sings in her voice and her eyes when she speaks about any of her creations.

The late Virginia McNeice

Founding VAM member Virginia McNeice, 82, died on March 12, 2019, surrounded by her loving family. Virginia was the beloved wife of Donald McNeice. Born July 17, 1936 in Riverdale, N.Y., she was the daughter of the late Harold and Maude (Taylor) Paro. Virginia (Jini) attended Pratt Institute of Art in Brooklyn, N.Y., graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Fine Art. In 1966, the family moved from Huntington, Long Island to Cambridge, NY to pursue their dream of living on a farm with their family.

Founding VAM member Virginia McNeice, 82, died on March 12, 2019, surrounded by her loving family. Virginia was the beloved wife of Donald McNeice. Born July 17, 1936 in Riverdale, N.Y., she was the daughter of the late Harold and Maude (Taylor) Paro. Virginia (Jini) attended Pratt Institute of Art in Brooklyn, N.Y., graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Fine Art. In 1966, the family moved from Huntington, Long Island to Cambridge, NY to pursue their dream of living on a farm with their family.

Jini became a prolific and regionally-renowned landscape artist who drew inspiration from the natural beauty of the countryside she loved. Her work is in private collections, regional galleries, local hospitals and businesses. Jini’s art moved many people and even inspired some to begin their own artistic journey. Her artist friends valued her knowledge and insight, as she welcomed them into her studio and her life. As celebrated as she was in the art world, Jini accepted accolades with humility and grace. A quotation on her studio wall reads, “It’s the process, not the product”. Jini enjoyed being a vital member of the Cambridge community, Valley Artisans Market, Hubbard Hall, Battenkill Chorale, and the Agricultural Stewardship Association. Her calendar was always full.

Visitors to her studio were drawn to her gardens, which were one of her personal passions, and on hot days she would alternate gardening with dips in the pool. Jini and Don knew that gathering and growing their family around them was another expression of art in its finest form. Family extended far beyond blood relatives: they frequently opened their home to their children’s friends, young artists, and friends with shared interests. Jini was generous with cuttings from her garden, a quick art crit or a recommendation for a good book to read. The McNeice home was always open and the table always full. In the early years Jini and Don were proud to produce all their own food for the table, and in later years Jini always had a large vegetable garden, which she shared with family and friends and, to her great annoyance, woodchucks and rabbits.

Her children write, “Our mother taught us to see and appreciate color and light in the landscape around us. She taught us the pleasure of putting our hands in the dirt and making something beautiful. She encouraged in us her love of poetry and words, from juicy, descriptive phrases in a novel to a particularly witty wedding announcement in the Times, to a poignant line in a Mary Oliver poem. We learned to be curious and hardworking; to follow our passion; and to value family above all.”

Virginia was predeceased by her husband Donald of 54 years. Survivors include four children, Maggie McNeice of South Portland, Maine; Brian McNeice and his wife Jenny Ramstetter of Halifax, VT.; Kathy McNeice and her husband, JR Dugas of Cambridge; Annie McNeice of Cambridge; her sister, Diana Schleicher of Greenwich, NY; and many nieces, nephews and eight grandchildren. If you would like to remember Jini in a special way, the family suggests a donation to a Hubbard Hall or the Agricultural Stewardship Association.

New Member Emily Crawford

Emily Crawford dreamed of working as an undercover agent. She attended Hamilton College with the intention of being recruited to the CIA. But instead of becoming a spy, she pursued what she did best: art. She graduated with a degree in studio arts with a concentration in sculpture.

Emily knew she would find her way back to art, but first she had many other paths to follow. (During one of those paths, she worked as a website designer for 17 years. She helped design and build VAM’s website.) But after a recent job change, her attitude shifted. She prioritized art and career together.

She joined a friend at a class at the Saratoga Clay Arts Center in Schuylerville. When she put her hands back into clay for the first time in 30 years, she found her way back home.

“When you are an artist at heart, you are always creative in your life: the meals you make, the Halloween costumes you sew,” she says. But once she felt that clay, she didn’t want to get another job supporting creatives in their dreams. She wanted to put her artistic life front and center in her career, as well. She gave herself six months to delve deep into growing her own creative business. She rented a studio at Saratoga Clay Arts, built a web site, took classes for artists building creative businesses and began throwing clay. It worked. People are purchasing her work and she is refining it, and growing an learning more every day.

Her childhood home in Nova Scotia is the inspiration for her clay creations. “Everything I do is nautically inspired. I grew up going to Nova Scotia every summer and I stayed in our ancestral home. It is right on the Sissiboo River, off the Bay of Fundy.” The place she describes sounds magical. There are 40-foot tides, which allow for abundant beach combing. “On one beach, you have to walk a quarter of a mile to reach the ocean when the tide is out. There are all these tidal pools with seaweed floating around,” she says as she takes out a celadon green bowl, inspired by those pools.

In the summer the ocean is “a deep, deep green, almost an emerald. But then the ocean dramatically changes color from summer to fall. It turns a beautiful blue,” she says. She picks up a mug with colors graduating from black to a deep blue.

Looking closer at Emily’s pottery, one can see colors, textures and patterns based on the ocean. There are splashes and ripples, and mottled areas that look like sand. She points to drippy areas resembling waves lapping on the beach. The names of her pieces reflect her inspiration: Atlantic Splash, Sissiboo Tides, Beach Waves, Northern Lights, Fog.

Using Nova Scotia as her entry point into imagination and creation, Emily finds new ideas not only from the colors but also the shapes she sees. She makes “buoy bowls” that look like vases but the bottom resembles a buoy shape. On one of the buoy bowls, she pressed netting into the clay for texture. “I get so much inspiration for new textures in my work from beach combing.” And it’s hard to ignore the three-foot high sculpture of a lighthouse on her studio work table. If all goes well in the kiln, this piece will be the focal point of her upcoming show in the Small Gallery.

The lighthouse is simple, with just three flying birds etched into its side. She etches or paints the same birds into all the pieces she makes, a sweet reminder of the ocean and sand and tides. “That’s the core of who I am. The ocean – and my time in Nova Scotia – is my soul.”

In the future, she would love to create a Washington County series. She envisions visiting farms and using the inspiration she finds there to throw undiscovered shapes on her portable wheel. She hopes to join the ASA show and see the sale of her work go towards saving local farmland.

Her work may not involve the exciting life of espionage for the CIA but it fulfills her completely. She has never been happier.

Emily’s high-fire bowls, mixing bowls, mugs and other food-safe pieces are dishwasher- and microwave-safe. Emily has the next show in the Small Gallery, March 22-April 16. Her opening reception is March 30, 3-5 pm.

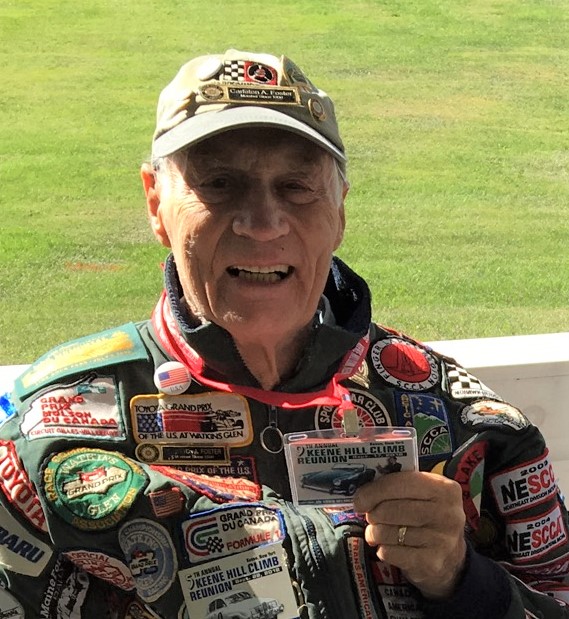

Founding member Carlton Foster

One of Valley Artisans Market’s founding members, Carlton Foster, passed away on Christmas Day, 2018. Though he hadn’t been a member for many years, we remember his humor and the wonderful craftmanship he brought to the market, selling his beautiful wooden utensils.

Carleton A. Foster, 83, of Jackson, passed away on Christmas Day, December 25, 2018 at the Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation at Hoosick Falls. Carleton was born a Shushan farm boy on September 20, 1935 and was the son of the late Anderson and Clara (Vaughn) Foster. He attended a two-room schoolhouse in Shushan and graduated from Salem Washington Academy. He had worked at Nash Rambler & Studebaker and also at Reynolds Tool & Die before starting his own business, “Puzzleworks” making children’s wooden puzzles. The business became C.A. Foster design & creator of fine cherry wood kitchen utensils and cherry wood sculptures.

Carleton was a charter member of the Valley Artisan’s Market, where his cherry wood creations were displayed and sold. He also was noted for the beautiful baritone voice and trained at the Troy Conservatory of Music. He was past President of the Washington County Historical Society and the Battenkill Snow Drifters. He was Past Master of the Cambridge Valley Lodge #481 F&AM Masonic Lodge; he was Lecturer of the Cambridge Valley #147 Order of the Eastern Star. Carleton also supported the Covered Bridge Association, the Cambridge Historical Society & Museum, the Historic Salem Courthouse.

He enjoyed Formula 1 racing and working at Lime Rock Park in Connecticut and also at Watkins Glen. Carleton did hill climb racing and was a Marshal for road races. He was noted at the Saratoga Auto Museum as a driver. He had a variety of interests which include painting and sketching and watching University of Connecticut Women’s Basketball. He started the annual tradition of the Shushan Bonfire.

In addition to his parents, he wa s predeceased by his first wife, Joan Tully Foster. Carleton is survived by his wife, Carol Brownell; his children, Lydia (Christopher) Owen of Columbia, SC and Hillary (Rev. Jarrett) Allebach of Worcester, MA; a brother, George Foster of Shushan; mother-in-law, Leta Tully of Cambridge; grandchildren, Vaughn, Aquilla, Blaize, Porsha, Ty, Wesley, Briana and Isaac. He is also survived by many nieces and nephews.

s predeceased by his first wife, Joan Tully Foster. Carleton is survived by his wife, Carol Brownell; his children, Lydia (Christopher) Owen of Columbia, SC and Hillary (Rev. Jarrett) Allebach of Worcester, MA; a brother, George Foster of Shushan; mother-in-law, Leta Tully of Cambridge; grandchildren, Vaughn, Aquilla, Blaize, Porsha, Ty, Wesley, Briana and Isaac. He is also survived by many nieces and nephews.

Donations may be made to:

Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation at Hoosick Falls Attn: Resident Fund

21 Danforth Street, Hoosick Falls NY 12090

The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research

Grand Central Station, P.O. Box 4777, New York NY 10163-4777

Welcome new member: Christine Levy

Christine Levy hunches over a white chicken egg. She sticks a quill in the flame of a candle to heat it then pokes the quill into a chunk of beeswax. As the smell of beeswax fills the air, she begins to write. Christine has been practicing her craft of Pysanka (traditional Ukrainian egg decorating) for more than 50 years. As a 2nd generation Ukranian, she learned her craft as a child, handed down through the generations. Her grandparents kept up with the traditions of the culture, especially dying and decorating eggs. “It‘s a clever folk art because it doesn’t take much to do it: beeswax, candle and dye,” she says. Christine begins with chicken eggs from local farms. Farm-bought eggs are better than store-bought because “they are stronger and take the dye better.” She uses a white egg that has not been hollowed out: a hollow shell is very porous and does not take dye as well as a full egg. Then she writes on the egg with beeswax. (The word pysanka comes from the verb pysaty, “to write,” as the designs are not painted on, but written with beeswax.)

Christine Levy hunches over a white chicken egg. She sticks a quill in the flame of a candle to heat it then pokes the quill into a chunk of beeswax. As the smell of beeswax fills the air, she begins to write. Christine has been practicing her craft of Pysanka (traditional Ukrainian egg decorating) for more than 50 years. As a 2nd generation Ukranian, she learned her craft as a child, handed down through the generations. Her grandparents kept up with the traditions of the culture, especially dying and decorating eggs. “It‘s a clever folk art because it doesn’t take much to do it: beeswax, candle and dye,” she says. Christine begins with chicken eggs from local farms. Farm-bought eggs are better than store-bought because “they are stronger and take the dye better.” She uses a white egg that has not been hollowed out: a hollow shell is very porous and does not take dye as well as a full egg. Then she writes on the egg with beeswax. (The word pysanka comes from the verb pysaty, “to write,” as the designs are not painted on, but written with beeswax.)

“Wherever you put the beeswax you are masking the color,” she says. “So I start with white then stick the egg in a light dye color like yellow.” She continues to write and mask more areas that she wants to keep yellow, then she dunks the egg into another dye color, working from light to dark. She keeps working until “[the egg] is black and covered with beeswax.” She removes the wax by sticking it in a toaster oven, though her ancestors would have held the egg over a flame to slowly melt off the wax.

Even after 50 years of creating, she still is enchanted and surprised when she removes the wax to see her creation. “You don’t know what it is going to look like. Every egg is different and takes dyes differently,” she says. When finished, Christine adds a coat of Polyurethene to make them shiny and also a bit stronger.

At this time of year, her decorated eggs can be used as ornaments on Christmas trees but they originated as an Easter tradition that is still alive and well in the Ukranian community. In her cultural tradition, one would make an egg as a gift where the pictures painted tell a story. Christine uses images like horses, which represent health and strength, and ribbons, which represent eternity and wisdom, on her eggs. “Deer and horses are my favorite images as well as flowers. It’s like handwriting – everyone has their unique handwriting and it’s the same for egg painting,” she says.

Ukranians also take pride in their ceramic work. “Many homes have a stove in the center completely lined with handmade tiles,” she says. Christine paints ceramics – porcelain and China – and has a lovely collection of pocket mirrors as well as small plates in the Market. To make the pocket mirror, she makes a pencil sketch then scans and prints it on thin plastic polymer. She fuses it to porcelain, like the back of the hand mirror, then decorates it with enamel paints. She fires it in an oven, not a kiln, until everything fuses to the porcelain.

“I love experimenting,” she says. “Every couple of years I feel like I am in a new zone. I just discovered last year how to get a really nice light green. I have been doing this for 50 years and I just figured it out. There’s also always something to learn.” Thankfully, Christine also teaches how to make her stunning eggs. “I love teaching because I don’t want to take all this knowledge with me.” Her ancestors would be proud.

Painter Rose Klebes

Rose Klebes paints every day. If she had her way, she would paint all day, every day. She usually sneaks in a couple of hours early in the morning in her studio, spending some time painting before she starts her day. During the warmer summer months, she is trying to paint outside as much as possible.

When weather permits, Rose is “plein air” painting, or painting in the open air. She loves this method of painting because “you have to paint fast to capture the light before it changes,” she says. “When I paint in my studio, I tend to overthink my work.” She might keep considering and re-considering a piece, changing it and reworking it, doubting her instinct. “It can go on for weeks before I complete a piece,” she says. “But plein air painting allows me to work quickly; these paintings are more pure because they haven’t been labored over,” she says.

Rose paints using acrylic and oil paints. She uses acrylic paint when she is working on a quick study. Since acrylic dries quickly, she will often bring a canvas and paint with her to Valley Artisans in order to paint during her shift. By the time the shift is over, she may have new work to add to her display.

But she loves working with oil paints because they are “thick and buttery and I like the way they handle and show brush strokes.” These days, she has taken to painting on Masonite, an engineered wood, which she seals in three coats of gesso. She loves the slick surface of Masonite as opposed to rougher canvas, so that paint moves around a lot more easily.

And she is inspired by everything around: by changing light, by dark on dark, by a little pop of color in an otherwise quiet landscape. But she loves painting nature most and she has the phenomenal ability of remembering what she sees. She can look at a scene one day and then recreate it the next day without looking at it again. Because Rose has been an artist for more than 40 years, she has worked in many media: woodworking and furniture, mosaics, weaving and even was a very successful watercolor artist with newspaper stories abut her work to prove it. She has tried her hand at sculpting and would love to explore it more.

But for now, the process of painting makes her more excited than anything else. “I always love whatever I am working on,” she says. She will be introducing new desings in the coming months and is excited to show them. She feels they show a lot of the confidence and that she has grown as an artist and it shows.

“If I didn’t create every day, there’s no reason to get out of bed.”

Arleen Targan

Arleen Targan, of Greenwich, was a long-time member of Valley Artisans. She had to resign several years ago when she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. We are so sad to announce she died on Monday, July 2, 2018. Our condolences go to her family, especially her husband, member Barry Targan.

Born Arleen Caplan on July 12, 1934 in Abington, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, her surname was later changed to Shanken when she was adopted by her grandparents. Arleen graduated from the Philadelphia College of Art and began her long and successful career as an artist, drawing portraits on the Boardwalk in Atlantic City. It was there that she met the love of her life, Barry, to whom she would be married for sixty years. They would go on to live, work, travel, camp, and sail in many places in the United States and Europe, spending much of their lives in upstate New York.

Arleen was a brilliant, gifted artist, excelling at many different art forms. She was especially known for her paintings of local landscapes and her portraiture at county fairs. Her granddaughters fondly remember numerous art projects with Grandma, who “made art fun.” Arleen’s creativity extended beyond the easel and into the kitchen. Always the gracious hostess, she delighted in preparing memorable meals for family and friends. Her love of the natural world was evident in the time she devoted to gardening, hiking, and swimming. A gentle, kind-hearted, and talented woman, Arleen will be deeply missed by her family and her many friends, including her fellow artists at the Valley Artisans Market in Cambridge, New York, as well as residents and staff at the Fort Hudson Nursing Center.

Arleen was a brilliant, gifted artist, excelling at many different art forms. She was especially known for her paintings of local landscapes and her portraiture at county fairs. Her granddaughters fondly remember numerous art projects with Grandma, who “made art fun.” Arleen’s creativity extended beyond the easel and into the kitchen. Always the gracious hostess, she delighted in preparing memorable meals for family and friends. Her love of the natural world was evident in the time she devoted to gardening, hiking, and swimming. A gentle, kind-hearted, and talented woman, Arleen will be deeply missed by her family and her many friends, including her fellow artists at the Valley Artisans Market in Cambridge, New York, as well as residents and staff at the Fort Hudson Nursing Center.

Arleen was predeceased by her parents, Harry and Ruth Caplan, and her sister Joan Shanken. She is survived by her husband, Barry, of Greenwich; son Anthony Targan (Holli Hart) of West Bloomfield, Michigan; son Eric Targan (Dollene Coolidge) of Belchertown, Massachusetts; and granddaughters Rebecca (Tomer) Dorfan, Alexandra Targan, and Hannah Targan. Those who wish to make a contribution in Arleen’s memory may make a donation to the Alzheimer’s Association or to a charity of your own choosing. To leave an online message for the family, please visit www.flynnbrosinc.com.

Basket maker Linda Corrow

Basket maker Linda Corrow was drinking cherry Kool Aid while sitting outside. That’s when she noticed that the hummingbirds wouldn’t leave her alone. They seemed to be attracted not only to the color of the red juice but also to the smell. She took the observation and applied it into her artwork, creating a small basket to use as a hummingbird nest. Since hummingbirds prefer small spaces for their nests and the shape of the basket provided not only a shelter but also a warm area due to its size and shape, they approved. But what they really responded to was the red lip on the opening. That’s because Linda dyed the reeds with red cherry Kool Aid.

Linda took up basket-making just 7 years ago. She was battling cancer and couldn’t work but was miserable sitting around the house focusing on how miserable she was. She tried to start some creative endeavors to occupy her mind. She took a painting class but hated it. She had always been curious about basket weaving so her daughter bought her a couple of basket-weaving kits. One was a kit with flat reeds and one included round reeds. She found that she not only loved basket-making but she had excellent finger dexterity and was successful at weaving baskets with the round reeds. She could turn, twist, pull, tug and manipulate the round ones much better than the flat reeds. The more she practiced the better she became. The better she was, the more she fell in love with the process.

She picks up one of her baskets and points to all the different weaving stitches that are in just one basket, each making a different pattern. She especially likes Japanese weaves because they are simple but she can modify them to make many new combinations of patterns. She has mastered locking reeds together to make an extremely durable basket that won’t fall apart, will sit flat and last a very long time. “These things are indestructible,” she says as she points to the lovely rounded bottom of one of her baskets. “You can throw it like a frisbee as far as you can and it will be just as strong.”

Not bad for someone looking for something to occupy her mind and her hands. The hummingbirds would agree.

Glass artist Cheryl Gutmaker

Glass artist Cheryl Gutmaker has run out of peacock green-colored glass. Since this color was one of the most popular in last year’s designs, it is frustrating that she can’t get more. Two companies that supplied the glass closed two years ago. A third company has no projected date for when they will manufacture this color again.

But Cheryl takes the challenge in stride. She has shifted gears many times in her life when she has hit speed bumps. She recreated herself after losing her job as a music teacher due to budget cuts. She beat cancer. And then she began a career in glass when others might have thought of slowing down.

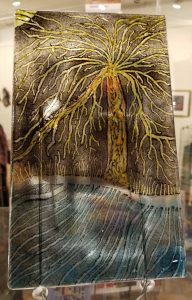

Cheryl has just returned from a four-day workshop at The Bullseye Resource Center in Mamareneck, NY. Her voice crackles with excitement about what she learned at this renowned glass center. “We played with different textures of glass in the kiln and experimented with firing different sizes of glass together,” she explains. “We explored what effect there would be if you fired the same piece at different degrees. How is it going to affect the material? How is it going to look different? How will the color change?” One of the thrilling parts of the workshop for Cheryl was playing with frit powder, or tiny bits of glass, that allowed her new possibilities in her artwork. “I have always wanted to make a weeping willow tree and never could get the effect until taking this glass course,” she says. (See photos )

)

She’s come a long way from her artistic beginnings. She began her career as a glass artist creating beads for jewelry. She forged them with a torch, glass rods and an annealing kiln. After accumulating baskets of beads, she looked for a new way to use her kiln. “I started making soap dishes because I could fit three in the kiln.” They were a hit. Now Cheryl owns seven kilns and uses the small annealing kiln to make handles for her large serving platters and bowls.

Recently, Cheryl has been experimenting with more complex techniques. Painting with glass – called frit paintings – intrigues her the most. Creating a landscape takes enormous planning and a wealth of knowledge about fusing glass. “If I put a bird on a branch, I have to figure out if I should fire the bird first.” Cheryl explains that glass will react differently at different temperatures. The juxtaposition of pieces of glass also impacts the eventual artwork because of the presence of differing amounts of copper, sulphur and lead. “I want a nice amber in the background but amber is very reactive so there has to be clear glass between the amber glass and other pieces,” she says. There are also a finite number of times you can fire glass. “Some glass can only be fired three times before it starts to break down, while others can be fired 25 times.”

Her knowledge is dizzying but she is constantly learning. Sometimes, the best lessons come from mistakes. “When I put on little bits [of glass], I use Superglue to tack them into place. Sometimes the glue burns off before I want it to and the glass slides a bit. I was doing eyes for crabs and they slid so that the crab came out with googly eyes.” Her customers loved them so much that she changed her design.

But for now, Cheryl is trying not to make any mistakes. She is busy creating inventory for the prestigious Paradise City Festival in Massachusetts in May, facing many happy hours fusing glass. If you own one of Cheryl’s creations with peacock green in it, consider yourself especially lucky. It may be a while before a matching piece will be available.